Over the past decade 360 leadership assessments have gained popularity as a way to evaluate the leader’s competence and potential, and to chart a course for his/her development. But what do these assessments really tell us?

To find out, let’s consider the research.

360 Leadership Assessments – What Self Ratings Tell Us

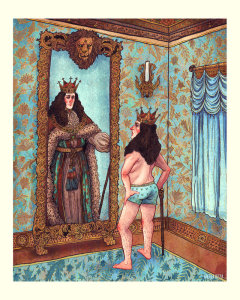

Self ratings correlate exactly 0.0 with actual performance (Lombardo and Eichenger 2003). It seems the leader, like the emperor, doesn’t see his new clothes as others do.

Self-ratings, however, are far from meaningless. They actually predict the likelihood of promotion, stagnation, and termination.

Lombardo and Eichenger tracked a group of leaders for two years after completion of their 360 leadership assessments. Three clear paths emerged when leaders’ self-ratings were compared to others’ ratings:

- Under-raters were most likely to be promoted

- Similar-raters were most likely to stay where they were

- Over-raters were most likely to be terminated

The reasons seem like not-rocket-science, but then again, I’m a leadership psychologist, not a rocket scientist.

Successful leaders are continuous learners. They know they need to learn and change as they move up. (For a thoughtful guide to what needs to change at each level, see The Leadership Pipeline, at the bottom of this post). Why do these star performers tend to under-rate themselves? They set higher standards for their own performance, seek more feedback, and rarely see themselves as measuring up. If and when they do, they raise the bar.

By contrast, higher self-raters have glaring blind spots, especially regarding their people skills. People skills is where the trouble begins and where it also ends the over-raters tenure in his/her current leadership role.

Lower level supervisors need to be skilled at managing projects, work and tasks – operational issues. But people skills become increasingly important as leaders move up. At higher levels the leader is creating an environment for others to perform well. Senior leaders also deal with more breadth and complexity. To do so effectively, they need input from multiple perspectives and buy in from a broad audience. This too, calls for people skills. Leaders who over-rate their people skills don’t see the need to learn more in this arena, don’t engage in learning, don’t learn, and don’t succeed.

Managers who overestimate their competence, also tend not to learn from mistakes, because they don’t see them as readily or they assign responsibility elsewhere. As expected, they also have difficulty recovering when they fall from self-perceived good performance. (Shipper and Dillard, 2000).

The Boss’s Ratings

It’s no surprise that the boss’s ratings are most predictive of promotion, or lack thereof. After all, the boss determines who moves up, who stays where they are, and who leaves.

What group typically assigns the lowest ratings? This varies depending on the instrument. I often use the Emotional Competence Inventory and Leadership Versatility Index. On the former peers offer the lowest ratings, so much so that the instruments makes a statistical adjustment in peer ratings. Direct reports provide the highest ratings of the Leadership Versatility Index. The boss, customers and others rarely offer the lowest ratings.

Why?

- Boss – Successful impression management aka “Managing up”; and if the boss hired you, he has a vested interest in your success, which may influence his perceptions and ratings

- Peers – Competitiveness

- Direct reports – ????

References

Eichinger & Lombardo, (2003). Knowledge summary series: 360-degree assessment. Human Resource Planning, 26(4), 34-44.

Shipper & Dillard. (2000). A Study of Impending Derailment

and Recovery of Middle Managers Across Career Stages. Human

Resource Management, 39 (4): 331-347.

Listening to ocean waves receding over stones.

Enjoying the spontaneous expressions of young children who haven’t yet learned to hide their emotions.

Taking in the scent of freesias, lilacs or salt water.

Enjoying the great, or not so great, outdoors and all variations of nature’s gifts.

At the gym.